People – and Places

3March 24, 2013 by Richard Crowest

Why Alan Bennett’s new play felt strangely personal – and why he picked the wrong targets.

It’s probably wise, as a general rule, not to overestimate your influence on the world at large. But when you hear that the latest work by one of the country’s best-loved playwrights takes aim at the organisation that’s provided most of your work for the last decade, and seems particularly exercised by exactly the kind of work you’ve been doing for them, it’s hard not to feel a sense of personal interest.

That sense only increases when you learn that the large, run-down country house in which the play is set bears a striking resemblance to Calke Abbey, a house at which you’ve done a great deal of work. Following the old adage that once is coincidence, twice is happenstance but three times is enemy action, you’re really forced to sit up and take notice when you learn that the name of this fictional house is Stacpole, just one letter short of Stackpole, the vast country estate in Pembrokeshire – lacking its house since 1963 – where you’ve just finished an 18-month project.

So what am I to make of Alan Bennett’s People, his counterblast against heritage culture, the National Trust, and the strange dark art in which I’ve earned a living for several years, “heritage interpretation”?

“I sometimes think that my plays are just an excuse for the introductions with which they are generally accompanied,” writes Bennett, in said introduction. That’s probably a good thing, as his arguments and sense of uneasiness about the heritage industry are rather better set out here than they are in the play. The initial “itch” that prompted the play was, he says, “being required to buy into the role of reverential visitor”. Here, as in much of the play, he seems to be scratching at a very old bite from a flea he picked up several decades ago, as that hushed reverence is something the Trust has been trying to eradicate as thoroughly as it does the insect pests that eat its historic fabrics. What’s far more interesting, and worthy of deeper exploration, is Bennett’s sense that at the end of a visit “I still found it hard to say what it was I had expected to find and whether I had found it.” It’s difficult to imagine how one might go about exploring that idea on stage, and so it’s no great surprise that the play eschews it, focussing instead on the whether the house should be handed over to the Trust, and how it’s presented to the public when, perhaps inevitably, it is.

The question that’s sadly ignored is why such houses and their contents should be preserved at all, and why we should want to visit them when they are. For decades, National Trust house visiting consisted almost entirely of a leisurely wander through a series of mummified rooms, their architecture, paintings and furniture deemed sufficient inducement for us to part with our entrance money or membership fee. And I have to say, in its way, it worked. I think that for many years what I wanted from a visit was exactly what I got – an indoor equivalent to a stroll through the parkland outside, a chance to relax in an aesthetically pleasing, planned environment. Occasionally a painting or a piece of furniture might pique my interest, and I’d ask the attendant about it, prompting them to dive into the room folder. Invariably, the object of my interest was the one piece that the curator had deemed unworthy of their attention, and I left none the wiser.

The Trust’s guide books weren’t much better. Following a dense essay on the history of the family that you couldn’t hope to digest during a visit came the “Tour of the House” section, a room-by-room inventory of selected artworks and items of furniture, aimed squarely at a NADFAS (National Association of Decorative and Fine Arts Societies) audience. There was little here for the casual visitor, and even if you were interested in a particular item, the task of tracking it down in the unillustrated text was seldom easy.

But that was the Trust of 20 or 30 years ago, and the last decade has seen some radical changes. There’s been the over-eager throwing back of the barrier ropes as part of the “Atmospheres Project”, launched to rather disastrous effect on breakfast television, leading some visitors to dive headlong into every cupboard and closed door, brushing aside horrified room stewards with cries of “We’re allowed to now, they said so on the telly!” Fires are lit in grates, visitors are invited to sit in (some) chairs and read (selected) books. But more significantly, the Trust has started to recognise that one of the areas of greatest potential interest to visitors is the one they’ve been neglecting – the stories of the people, hidden away in that dense essay at the front of the guide book.

It’s time for a confession. Until I was writing the film and exhibition for Knole, I don’t think I’d ever read one of those essays. Thankfully, I started with a corker – the story of Knole and its family, as told by the present Lord Sackville, Robert Sackville-West, was a revelation, full of life and colour. For the casual visitor, it has to be said that the house itself could be something of a disappointment. Just thirteen rooms of this vast Jacobean mansion were open to the public, and the drab, dusty furniture they contain looks as if it’s been neglected for centuries. But the stories of how that furniture came to be there, and the extraordinary characters who collected it and put it on display to show their status and connection to royalty, are fascinating. To make a visit to Knole more engaging, it was the people, not the objects, that we had to put centre-stage. But here, Bennett seems to want the Trust to ignore the most… interesting… storylines. He imagines the organisation as “entirely without inhibition, ready to exploit any aspect of the property’s recent history to draw in the public, wholly unembarrassed by the seedy or the disreputable”. He depicts this by having the Trust include a scene from the porn film shot during the play in the interactive video presentation installed at the fictional Stacpole. But at Knole, long before the arrival of the Trust, it was the family who displayed the voluptuous nude statue of Giovanna Baccelli, the Italian dancer and mistress of the third Duke of Dorset, who bore him an illegitimate son. (In yet another coincidence, Knole’s history began in 1456, the same year Bennett gives to the founding of Stacpole.)

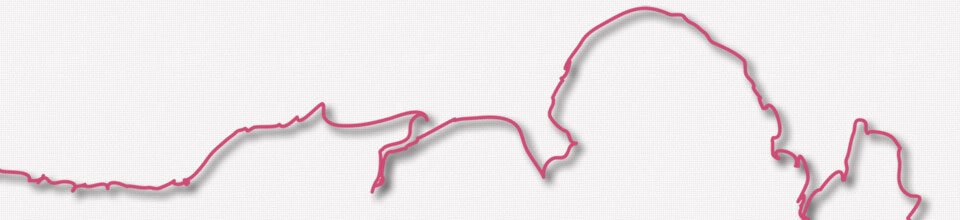

At the real Stackpole in Pembrokeshire, the family’s story is yet more outlandish. We tell only a tiny part of it in the exhibition there, as the estate is now a nature reserve, and without the house there is limited space. But that very absence needs explanation, and the tale is a dramatic one. Like Bennett’s Stacpole, this estate lost land during World War II, when the MOD compulsorily purchased much of the best agricultural land to create the Castlemartin Firing Range, whose ordnance still rumbles menacingly through the valleys, much like Stacpole’s shaky seam of coal. The house suffered, too – the familiar story of a wartime billet, vandalised and stripped of the lead from its roof. Hugh Campbell, later sixth Earl of Cawdor, was given the impoverished estate on his 21st birthday, and applied to the council for a grant to reduce the sprawling Victorian house to its more manageable, Georgian proportions. When they refused, he simply sold off the contents and, in a fit of pique, had the house bulldozed, selling the rubble for foundations at Milford Haven oil terminal in a final two-fingered gesture to the people of Pembrokeshire. This much you can glean from a visit to Stackpole. But Hugh’s daughter, Liza Campbell, has told their story in far greater detail, in her book Title Deeds. Bringing down the house, it transpires, was far from the peak of the sixth Earl’s tempestuous lifestyle: alcohol, a string of mistresses, a live-in aikido instructor, wife-beating, attempted incest and seven wrecked Jaguars must be added to the roll. If families are unembarrassed by the “seedy or the disreputable”, why should the Trust be on their behalf? Bennett almost seems to suggest that it should act as a moral conscience for the nation’s history, presenting only those parts that are wholesome and seemly. I can’t imagine I’m alone in finding that a little odd, coming from the writer of works such as Kafka’s Dick and the screenplay of Prick Up Your Ears. Bennett has Lumsden, his representative of the Trust, say that “there is nothing that cannot be said, nowhere that is not visitable. That at least the Holocaust has taught us.” It’s clear from the play, and the introduction, that we’re supposed to find this attitude distasteful, at the least. But what an astonishing sentiment from a writer. I won’t insult Bennett by suggesting for a moment that he’s saying we shouldn’t tell the story of the Holocaust. But there is an order-of-magnitude difference between being told a story and seeing the place where it happened – the gas chambers, the piled-up, unnumbered shoes of the dead. Can it be that Bennett has bought into the role of “reverential visitor” at least far enough to believe that visiting a country house should embrace nothing beyond the genteel, no matter what the underlying truth may be?

The most extraordinary feature of the fictional Stacpole is its collection of chamber pots, complete with the micturitions of a gallery of billiard-playing Edwardian luminaries. Lumsden is understandably cock-a-hoop at the discovery of such an eccentric survival, each one neatly labelled to indicate the owner of the bladder from which its contents flowed. What Bennett doesn’t permit Lumsden to do, though, is what anyone in his position surely would do in such a situation: to ask some very searching questions about the kind of family that would want to collect Rudyard Kipling’s piss in the first place, let along hang on to it for four generations. At Knole, a close-stool used by Charles II or James II is proudly on display, providing further evidence of the family’s intimacy with the royal family. At Stacpole, the question I’d want answered is not “whose” but “why”. For most families, a visitors’ book provided sufficient insight into the standing of one’s social circle, and allowed one to stay effortlessly po-faced.

While Lumsden does, at the end of the play, stray into the territory of telling “the story of the house”, even providing a role for Lady Stacpoole, in most respects Bennett’s portrayal of the Trust’s work is decades out of date (much like the play’s one gay character, who seems to have strayed from the set of a 1980s sitcom). The house itself is magically restored – “the transformation should be spectacular,” says a stage direction. But that would be very unlikely to happen now. Calke Abbey, which I mentioned earlier, was “saved for the nation” by virtue of an extraordinary provision in the 1984 budget, which stumped up the money for the endowment the National Trust needed to take on the house and estate. If you visit today, you’ll find many of the rooms looking exactly like Bob Crowley’s set for Stacpole at the start of the play. They are piled high with discarded toys, old furniture and cases of stuffed animals. The house was an extraordinary testament to the interests and eccentricities of the family that owned it, and that’s how it’s been preserved. The Trust’s fastidiousness in halting, but not reversing, the decline even extended to reinforcing the peeling ends of wallpaper so that they remained hanging, but peeled no further. One of the jobs we undertook for the Trust there was to set visitors’ expectations before they went into the house, as a frequent comment used to be “It’ll be lovely when it’s done up”. Much of the public remains very attached to the notion of restoration as depicted in the play – at the real Stackpole, one comment from a consultation exercise recommended rebuilding the demolished house, with the comforting addendum that the writer was sure the money could be obtained from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The National Trust seems to have become the lightning rod for Bennett’s ire simply by virtue of being the largest and most visible pedlar of the heritage visitor experience. Many of his criticisms could equally be applied to those houses still in private hands that are thrown open to the public gaze in order to fund their continued existence, such as Burghley, which rather inexplicably featured prominently in the short film that preceded the National Theatre Live broadcast of the play. There are many issues over which one might cavil with the Trust – its recent re-branding, that makes it feel corporate and commercial, determined to part you from your money or convert you to a member at every opportunity; its penchant for expensive top-down reorganisations that seem hell-bent on stripping its ranks of everyone who actually understands what visitors want and need. Yet the one thing that Bennett chooses to criticise is the simple desire to open a house to the public, and allow people to understand its rich and complex story.

“People spoil things,” says Bevan, the valuer trying to persuade Lady Stacpoole to keep the house out of the clutches of the Trust, and hence the public. But people need to experience and understand things if they’re to appreciate them, and so deem them worth preserving. This is the part of the equation that Bennett never explores, beyond listing the possible future uses of the house that have, fruitlessly, already been explored. Dorothy Stacpoole longs to be able to take the house for granted, but lives in a couple of rooms, unable to pay for the upkeep of a sprawling building with no purpose other than as a repository for her memories. It’s a story that was repeated hundreds of times across the country in the mid-twentieth century, but often with demolition as the dénouement (rather giving the lie to Bennett’s line that it was in the 1980s that we stopped being able to take things for granted). That tide of destruction has left us as a nation unwilling to countenance the loss of any of our built heritage (or at least that aesthetically pleasing part of it built before World War II – latecomers fare less well in the heritage beauty pageant), seemingly almost regardless of its merit, uniqueness or usefulness. It’s not surprising that Lumsden tells us that “there is a school of thought on my committee that thinks we have enough country houses as it is.”

To survive as visitor attractions – which is what these places are, however vulgar one might find the phrase – country houses must add to the overall story of Britain and its people. The one refrain in People that rang utterly false for me was Lumsden’s hymning of Stacpole as a metaphor for England. I’ve met no-one in the Trust who thinks of houses in those terms. They are at best windows into a tiny part of its story, and through those windows we gain a fleeting glimpse of the lives of privileged families and the people who made their estates function and prosper. Dorothy longs to be left alone to enjoy the house in which she’s spent most of her life. It’s a pang many National Trust donors must share, and, of course, it’s a privilege which no visitor ever gets to enjoy. During the making of the film at Knole, I briefly found myself utterly alone in the Leicester Gallery when the crew went to get some equipment from the van. An inexpressible stillness descended, and I felt as though some distillation, some essence of the house’s five and a half centuries, began to seep from the walls. It didn’t speak of stones, or timbers, or art or furniture. It spoke, ironically, of people.

Category Arts, Heritage, Review, Theatre | Tags: arts, heritage, theatre

What an insightful, well thought out, response to Bennett’s play. (Of course it helps to have actually seen it!)

Thank you for an extremely interesting take. I haven’t seen People, and have no inclination to spring to Bennett’s defence – I find late Bennett, in several respects, highly frustrating.

But one important caveat: you write: “Bennett almost seems to suggest that it should act as a moral conscience for the nation’s history, presenting only those parts that are wholesome and seemly. I can’t imagine I’m alone in finding that a little odd, coming from the writer of works such as Kafka’s Dick and the screenplay of Prick Up Your Ears.”

Kafka’s Dick is a play about the unseemliness of the public’s interest in writer’s lives, and expresses contempt for the biographer or reader of biographies who is more interested in the size of Kafka’s dick than in what he wrote. The message of People, as you interpret it, sounds like a development of that argument: nothing odd there. (As for Prick Up Your Ears: it may be that Bennett felt that Orton’s exhibitionism and notoriety made it OK. Or it may be that, the film having been made more than a quarter of a century ago, he has since changed his mind.)

Thank you – a valid point.